I want to acknowledge the passing today of two unique voices. It was my synchronistic good fortune to have enjoyed encounters with both, back in the day.

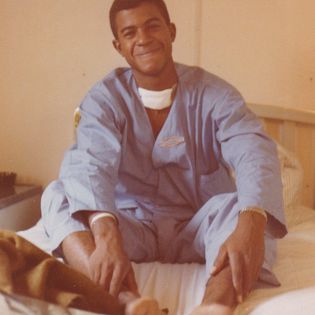

I resigned my Army commission after Vietnam in 1970 and moved to New York to study acting. Sanford Meisner, a seminal teacher of ‘The Method’ (along with Stella Adler and Lee Strasberg) headed the acting program at the Neighborhood Playhouse, located on East 54th Street in Manhattan. In addition to receiving the guidance of a man responsible for shaping so many acting careers, students benefited from artists who returned, to give back and to motivate new aspirants. During my tenure, such visitors included Maureen Stapleton, Tony Randall, Anthony Zerbe and Roscoe Lee Browne.

Zerbe and Browne already enjoyed important careers in film and theater, but shared a passion for the Spoken Word and for poetry. Over the years, between gigs, they toured the country, offering performances of their own work and the words of writers like Dylan Thomas, e.e. cummings, Amiri Baraka and Richard Wright. Their visit to the Playhouse was entertaining and inspiring, especially to me. Bear in mind that in 1971, unlike today, successful actors of color were very few and far between.

Roscoe Lee Browne had a courtly presence, a mellifluous baritone voice and a mischievous twinkle. His manner was elegant, rather old school and his diction precise and dramatic. He once recounted that early in his career, a director told him that his speech sounded ‘white’.” His response was disarmingly simple: “We had a white maid.” While perhaps not best known for his poetry, the passing of Roscoe Lee Browne is a loss for all who cherish elegant expression.

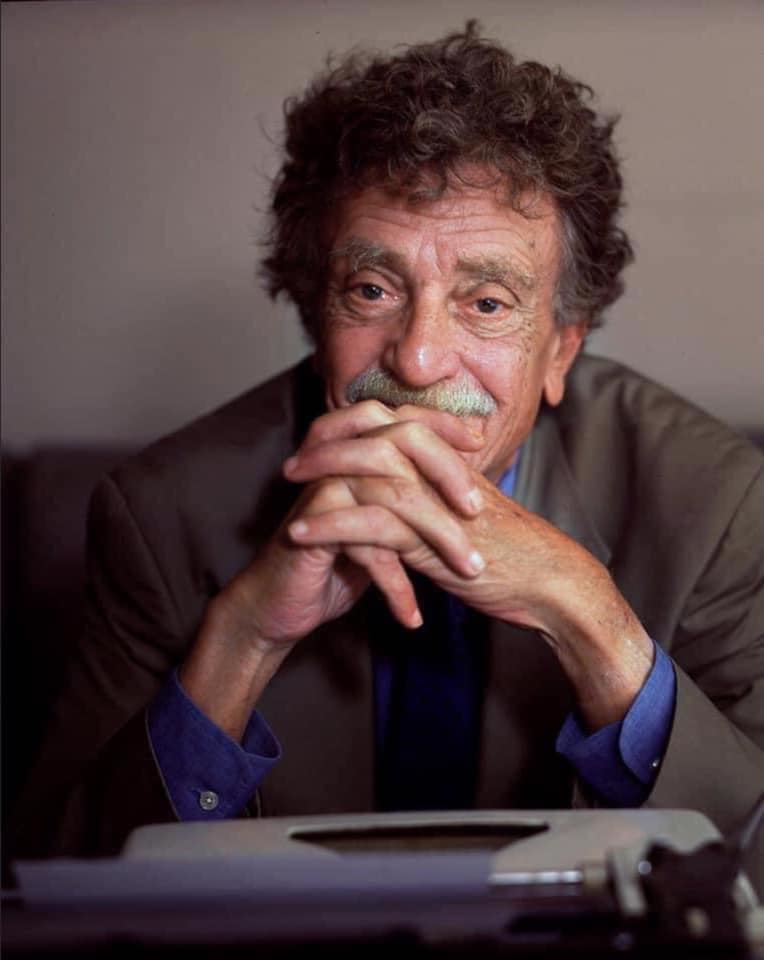

Often during breaks between classes, Playhouse students would hang out on the stoops across the street, enjoying a coffee or a smoke. One afternoon, I noticed a man approaching, someone I instantly recognized from his book jacket photos. He was one of my favorite authors (along with Joseph Heller, who’d written CATCH-22) and I immediately rose and introduced myself to Kurt Vonnegut, expressing my admiration of his work. Kurt lived with his wife in a nearby brownstone and enjoyed daily walks around his Upper East Side neighborhood. He was gracious and stopped for a few minutes to chat with me.

I’d learned to read when I was three and before reaching my teens had become passionate about science fiction. I discovered we had more than a few things in common, sharing an affection for the work of Asimov and Ray Bradbury. His perceptions were informed by his experiences during WW II. He’d served as an Infantry scout during the Battle of the Bulge, was captured and eventually interned in Dresden as a P.O.W. Tho Dresden was hardly a military target, the Allies decided to firebomb the city, destroying countless art treasures and killing at the very least, 35,000 civilians. The true total of casualties remains in historic dispute; suffice it to say, ‘payback is a mutha.’ The POW’s survived, simply because they were imprisoned in an underground meat locker, a ‘kuhlschrank’, a slaughterhouse. Kurt and others were later put to work, extracting those countless corpses from the ruins and burning them, in large funeral pyres.

I’d also served in the Infantry, commanding an advisory team in the Mekong Delta. Infantrymen, like Marines and other grunts, feel an instinctive bond, knowing that our job description generally puts us on the cutting edge of combat. The mission of the Infantry: “To close with and destroy the enemy, thru fire and maneuver”. We are accustomed to having our faces in the mud, and dealing with the enemy, up close and personal. Kurt and I were both awarded the C.I.B. (Combat Infantryman’s Badge) and the Purple Heart, which are my two most valued decorations.

We didn’t speak of war that day, but I did discover that we shared something else in common – a preference for a particular brand of unfiltered cigarettes, rather difficult to find these days. They are called Pall Mall, and their slogan: “Wherever Particular People Congregate.” They are the only brand I’ve ever smoked and if they’re ever discontinued, I’ll probably manage to surrender a 46 year-old habit. In his recent years, with characteristic humor, Kurt considered suing the makers of Pall Mall, saying “On the package they promise to kill me… and they still haven’t done it.”

Kurt’s novel, Slaughterhouse Five (which was later filmed) was released in 1969. I’d read all of his earlier work and been entranced with his combination of science fiction, social commentary, irony and whimsy, books like Mother Night, Player Piano and Cat’s Cradle…but Slaughterhouse Five was an effort to articulate his life-altering experiences during WW II. Ironically, the Vietnam War was the catalyst that freed him – not to write a story about war, but simply to tell the truth.

In his own words: “Finally to talk about something bad that we did to the worst people imaginable, the Nazis. And what I saw, what I had to report, made war look so ugly. There is nothing intelligent to say about a massacre. Everybody is supposed to be dead, to never say anything or want anything ever again. Everything is supposed to be very quiet after a massacre and it always is… except for the birds.”

“I have told my sons that they are not, under any circumstances to take part in massacres and that the news of massacres of enemies is not to fill them with satisfaction or glee. I have also told them not to work for companies which make massacre machinery and to express contempt for people who think we need machinery like that.”

We shared another cigarette and at some point, classmates reminded me that our next school period was about to begin. I shook his hand and thanked him for our conversation. Over the passing years, I continued to enjoy his prose but I never forgot those few minutes spent in the company of an artist who knew and aptly expressed the insanity that is often a consequence of war.

“So it goes….”

11 April 2007