Veteran actor draws from deep well of experience

You might not recognize Tucker Smallwood’s name. But there’s a good chance the voice is familiar. Same with the face. Maybe even the eyebrows.

Just ask Bryttani McGhee, a theater arts student at California State University, Fresno, who appears with Smallwood in the current production of “The Piano Lesson.” “I’m a ‘Star Trek’ fan, and even though he wore all that makeup on the show, I recognized him instantly by his eyebrows when I met him,” she says.

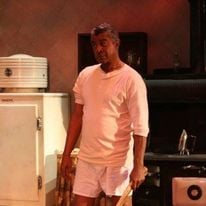

Tucker Smallwood appears in Fresno State’s “The Piano Lesson.” Yes, even Smallwood’s countenance has an identifiable intensity all its own.

Smallwood has played a lot of memorable roles in a 37-year acting career, including a recurring role as Xindi-Primate on “Enterprise” (one of the many “Star Trek” spinoffs), the mission director in the film “Contact” and God on “The Sarah Silverman Program.”

He’s done thousands of voice-overs and TV commercials. He was the first actor of color to sign a contract on the CBS soap opera “Search for Tomorrow.”

On the stage scene, he studied under legendary acting teachers Sanford Meisner and Stella Adler. His New York theater career included six productions for Joseph Papp at the Public Theater.

And now, he’s devoting his considerable stage presence to director Thomas-Whit Ellis’ production of “The Piano Lesson.” As a visiting guest artist, Smallwood is dividing his time during his monthlong stay at the university between acting the role of Uncle Doaker and lecturing to different classes.

You might think all this is routine for the 65-year-old Smallwood — that he’s carved out a comfortable gig in recent years visiting various college campuses and added luster to the local marquee while imparting his career wisdom to students.

Actually, it’s new for him, too. “This could be the next thing for me,” he says, sitting outside Fresno State’s student union last week luxuriating in a sunny morning. People make general life-changing statements like that all the time, especially when speculating about the future. But even though we met just the night before at a “Piano Lesson” rehearsal, I get the sense that when Smallwood puts his emphatic mind to something, it’s more than just small talk.

This is a man, after all, who exudes an almost palpable intensity. Whether he’s barreling through (in those sonorous tones) career news about his latest film, the Sundance selection “Black Dynamite,” or musing in eloquent terms about Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, one of his passionate causes, he instills in nearly every phrase a sense of vigor — along with hearty self-confidence. (Noting that he’s been conducting question-and- answer sessions with students in various Fresno State classes, he says, deadpan, “I’ve been really peeved that I haven’t been taping them, because I’ve been brilliant.”)

Before he was an actor , he was a TV director — and then a soldier. Grievously wounded in the Vietnam War, he was pronounced dead on the operating table. But he held on. After months of convalescence, he opted for a career change: actor. And from then on, he pounded out a living on stage, film and TV.

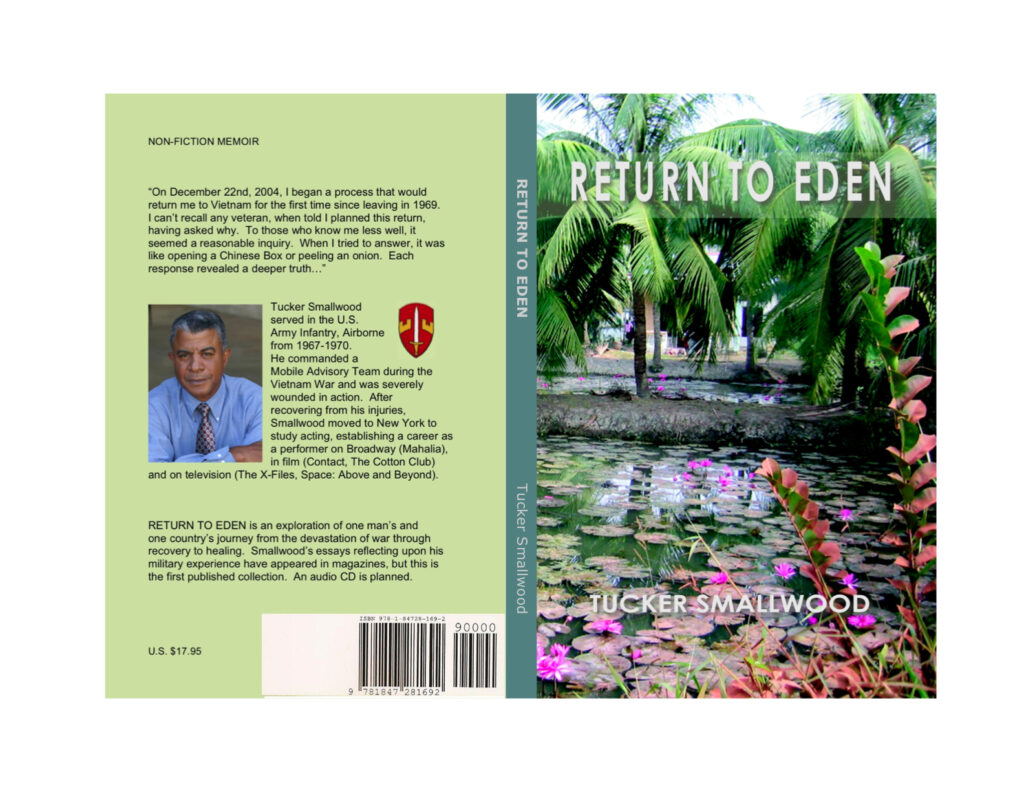

There have been setbacks along the way — most notably a years-long chunk of time lost to PTSD, the condition that affected so many Vietnam War veterans. He has it under control now, but still speaks out about it to veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars and their families. “You can’t ask these men and women to do these things for their country, then have them come home and just give up on them,” he says. Along the way he wrote a book, “Return to Eden,” an anthology of stories about his time in Vietnam and his return to that country in 2004.

Though he has continued over the years to work hard and often in Hollywood — mostly guest-starring roles on TV series and the occasional feature-film character part — Smallwood admits that it hasn’t always been easy. “People have never known what to make of me,” he says. He rarely gets cast as father or lover, but more often as an authority figure. Something about his aura suggests a smooth, commanding competence. What’s more, he doesn’t fit into the usual “ethnic” role, even though in many ways he’s been a groundbreaking actor of color. For example, he’s never even auditioned for one of August Wilson’s celebrated plays, which focus intently on African-American life and are considered prestige roles for black actors.

Yet when I watch him on stage during one of the final rehearsals, it’s clear that the role of Doaker — the uncle trying to keep peace in his house between his warring niece and nephew — is a natural for him. Woven into Wilson’s Pulitzer-Prize winning play, set in 1930s Pittsburgh (and revolving around a family heirloom piano), are such textured themes as family loyalty, constancy and balancing the memory of slavery with the optimism and challenges of a changing society.

What’s fascinating is to see how much Smallwood’s professionalism elevates the performances of the student actors around him. Sure, it’s been a little intimidating for some of them — who wouldn’t gulp a little when acting opposite someone with Smallwood’s experience? — but the impact is fierce.

“When he came in the first time, he was the character,” says McGhee, who plays the niece, Berniece. “I had to focus myself and tell myself, ‘I’m Berniece right now, not Bryttani.’ ”

Ellis, who is directing his first Wilson play at Fresno State since “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” in 2000, remarks that he and Smallwood have engaged in a fruitful “good cop-bad cop” routine with the students, with Smallwood’s professionalism keeping everyone on their toes. How intense is the whole acting experience for Smallwood?

That feeling of being in the moment, of everything happening at once, of open-ended possibilities — it reminds him of one thing. “It’s the closest I’ve come to combat,” he says.

Which, perhaps, is why he’s considering more adventures in higher education.

Yes, he says, he’s a little tired. Like a horse that has been ridden hard and put away wet. It’s a good tired, but it’s still tired. More than that, he loves the chance to pass on his experiences to a younger generation.

“I tell them I am a book,” he says. “They just have to open it and ask the questions.”

And with that, he raises one of those famous eyebrows ever so slightly and heads off to class.

Sunday, Mar. 01, 2009

By Donald Munro / The Fresno Bee